The king Frederick William III also went to Vienna, although he developed his role behind the scenes. Prussia represented by the Prince Karl August von Hardenberg, the Chancellor, and by the diplomat Wilhelm von Humboldt.The Tsar had two main objectives: to gain control of Poland and to promote the peaceful coexistence of European nations. The Minister of Foreign Affairs, Count Karl Robert Nesselrode headed the Russian delegation. Russia represented by the Tsar Alexander I.Britain represented first by his Secretary of Foreign, Viscount Castlereagh after, by Duke of Wellington, Arthur Wellesley.The Emperor Francis Ifollowed the whole developed of the congress.

Austria represented by the prince von Metternich, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, and his assistant, Baron Johann von Wessenber.Count Gustav Ernst von Stackelberg Main participants: Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord 23. Friedrich von Gentz (Congress Secretary) 19. Richard Le Poer Trench, 2nd Earl of Clancarty 17. Pedro Gómez Labrador, Marquis of Labrador 16. Pedro de Sousa Holstein, 1st Count of Palmela 10. Jean-Louis-Paul-François, 5th Duke of Noailles 6. António de Saldanha da Gama, Count of Porto Santo 4. Joaquim Lobo Silveira, 7th Count of Oriola 3. Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington 2. The leadership of the Congress fell on the four powers that defeated Napoleon: Great Britain, Austrian Empire, Russia and Prussia. The Congress of Vienna (1814-1815) was the largest diplomatic meeting held until then in Europe. There were countries where the restoration of the old order was impossible while in others, in some way, it was easier. The revolutionary past left a deep footprint in Europe. Not all Europe behaved the same.

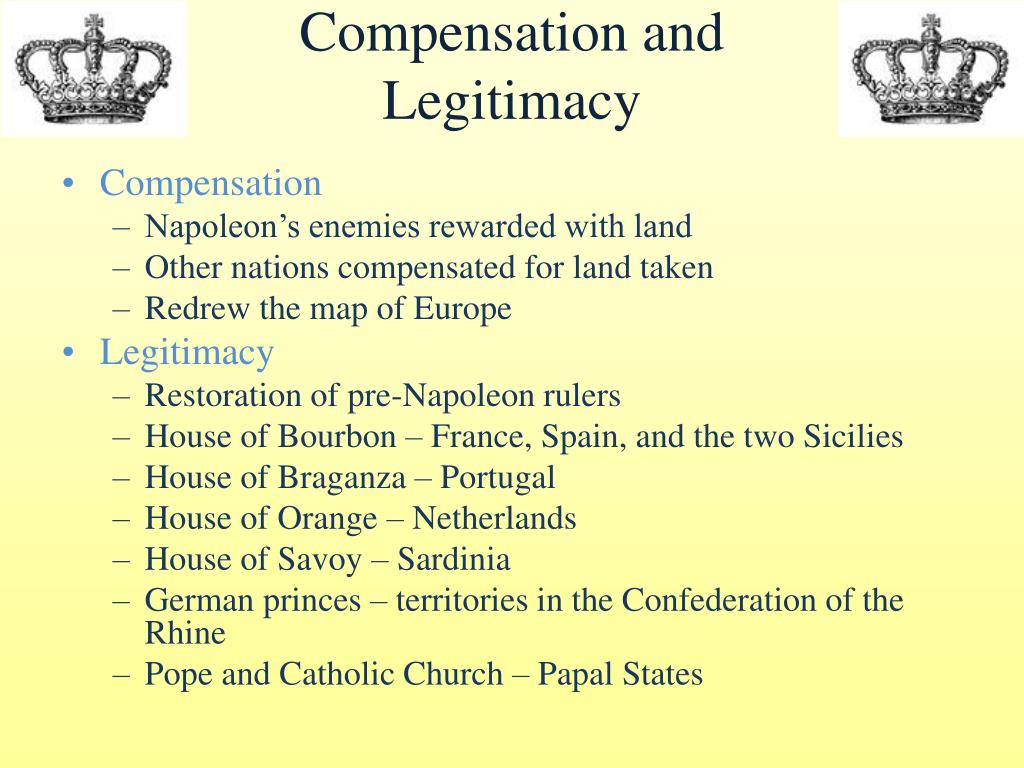

The restoration of the old regime that the monarchies claimed was impossible. Society based on privileges, not equality. Restore powers where the monarch and his government did not share sovereignty with parliaments. Monarchy based on tradition, which opposed the idea of the Nation as a popular will. In the time of the Restoration, between 18, it was based on the following principles: The Congress of Vienna was the attempt of the absolutist monarchies to return to the pre-revolutionary era and to establish a "stable" order to their interests, which would stop the wave of the liberal revolutions. After the convulsive period of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic wars, the previous political and social order had to be reconstructed, to return to the old European order. A new geopolitical map of Europe and the absolutist restoration after the Congress of ViennaĪfter the defeat of Napoleon, the European powers tried to restore the past: the absolute monarchy and the estates' society. Austrian statesman Klemens Wenzel von Metternichwas the main protagonist. The Congress met at Schoenbrun Castle between Octoand June 9, 1815. The Congress of Vienna was the conference between ambassadors of the greatest powers in Europe. The congress took place after the seizures provoked during the Napoleonic Era throughout Europe, in which the French Empire will redraw the borders of the continent in its favour, and once Napoleon was defeated in 1814. The European powers had the mission to re-establish the political map, try to control and eliminate the liberal revolutions that they had produced or would have occurred in the future, and to re-establish in power the absolute monarchies that General Bonaparte had overthrown from power. The Congress mission was restoring European order after the defeat of Napoleon in Waterloo. The Holy Alliance contained conservative ingredients, but the liberal and provocative elements stood out-these were however suppressed within a few years by political appropriations by other statesmen.The Congress of Vienna was chaired by Prince Von Metternich, and it met in Vienna between Octoand June 9, 1815. Based on new archival evidence, it will transpire how both Prussian security experts and French semi-scientist scholars contributed to the design of the Holy Alliance. Subsequently, the origins and constitutive elements of the plan are delineated in order to demonstrate that it was a revolutionary amalgam of Christian pietism, semi-scientific Enlightenment theories, and a dose of modern, bureaucratic state centralism. To make this point, the chapter reconstructs how this “secret plan” came to be understood as “conservative” and how this reading of the Holy Alliance Treaty was influenced by latter-day interpretations and machinations far more than by its concrete substance at the time. This chapter argues that tsar Alexander’s Holy Alliance of 1815 was far less conservative and far more revolutionary than it was later understood to be.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)